Startup culture promotes organizational strategy that emphasizes open communication and has a relatively flat hierarchical structure, the primary benefit being a less stuffy work environment. Stereotypically, this laid-back vibe is usually accompanied by amenities ranging from office happy hours to video games to ping pong tables and beyond.

On the surface, it’s the ideal workspace, an area in which frequent breaks aren’t just allowed, but encouraged. As long as you get your work done, you’re free to do as you please. With just 15% of 2015 graduates preferring a job at a large corporation it would seem that this Disney World-ification of the business world is beginning to stick. That said, when these practices are implemented, reality doesn’t always live up to the ideal.

For all of startup culture’s attempts to make the workplace fun, they often run into various issues regarding, you know, business. When a company spends money on cool perks, this often means one of two things. On the one hand, it’s possible that the company is doing so well that they have the extra cash lying around to host sushi lunches and have FIFA tournaments (more on this later). On the other, this can be a telltale sign of a company that’s mismanaging its finances and chasing a luxury office life that it can’t afford. There’s nothing sexy about balancing the books, but that’s the thing that keeps the lights on.

Some offices even offer their employees games – like foosball

Some offices even offer their employees games – like foosball

Sometimes though, the scenario is such that a company can provide all of the comforts associated with the typical startup without bankrupting itself. While it sounds great, this isn’t necessarily a good thing. Obviously, everyone wants their job to be fun. They want a flexible schedule that allows them to decide when and how their work gets done. But the problem is, when there isn’t a fixed schedule or the office is full of toys, it’s pretty easy to get distracted, and employees often end up working long hours to compensate for all of the nonessential work events. On top of this, when there isn’t a rigid hierarchical structure, people assume there aren’t rigid power dynamics. This is a mistake, and when the lines between boss and co-worker start blurring, it becomes a particularly difficult tightrope to walk. Especially since America puts a pretty low premium on work-life balance, and our social lives tend to be spent mostly with our coworkers. This intermingling can feel rather constricting, considering that it leaves very little time to not be on. It can also lead to nauseating conversations with not-your-managers in which they say things like I’m putting on my friend cap. The power dynamics in this world tend to resemble that of a school playground rather than the fixed, almost militaristic structure of 20th century corporate America.

This isn’t the only way in which startups buck corporate trends. While they lack in work-life balance and financial stability, startups make up for this by providing people the opportunity to be a part of something from the get-go, allowing people to feel as though they’re an integral part of their team. As said and repeated ad nauseum, millennials want jobs that give them purpose, and startups are particularly good at facilitating this desire. This changes the fundamental structure of what a work environment is. Work is no longer a place where one goes and receives payment in exchange for his/her services. The world of the startup is predicated on making its workers’ jobs an extension of themselves.

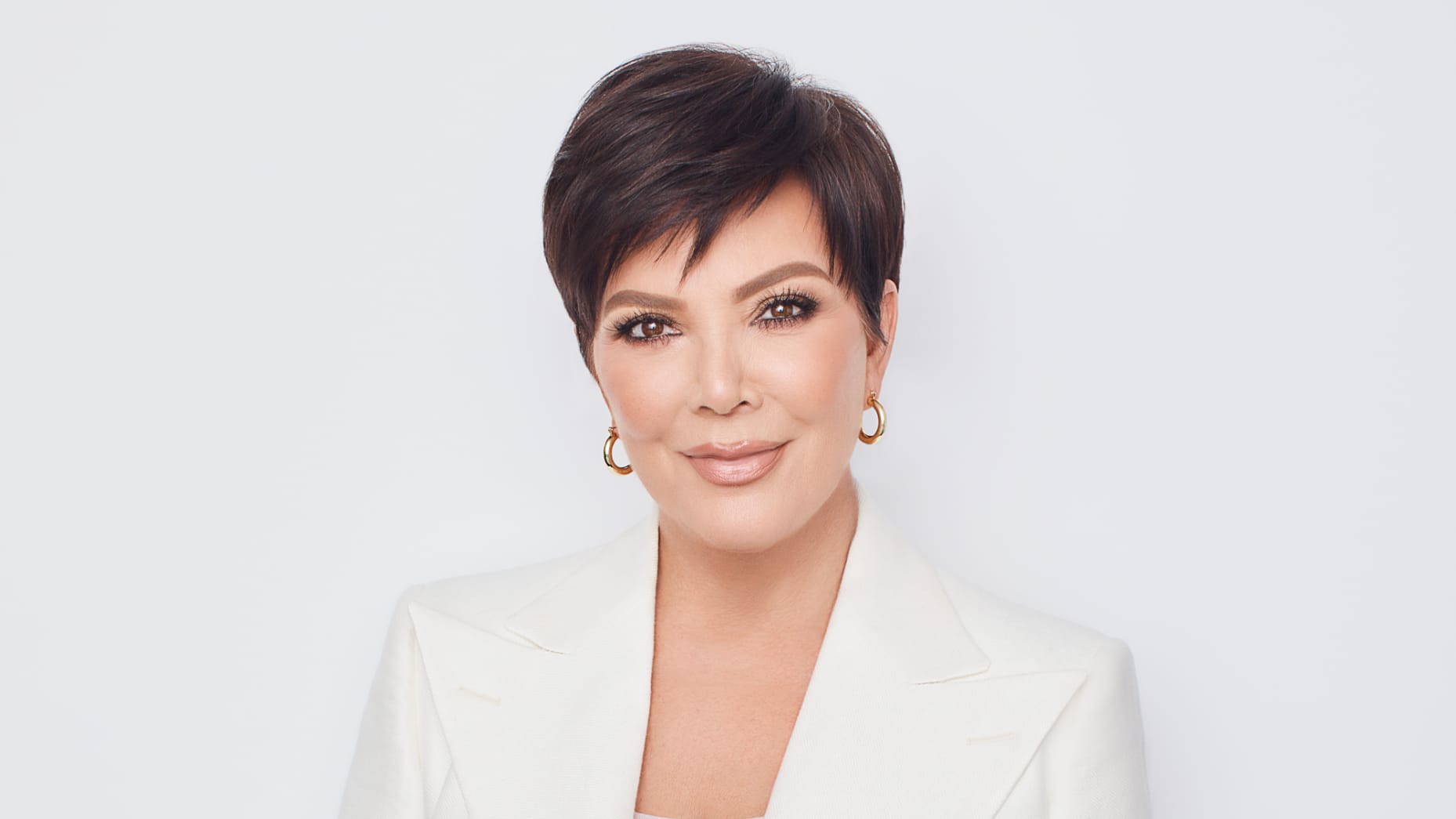

Team building at the office

Team building at the office

The 2017 film The Circle, while so terribly written that it may have destroyed Emma Watson’s career, attempts to deal with the problem surrounding tech companies and the cult of personality that tends pervade within them once they hit critical mass. If you ignore the plot, horrible acting, and bad writing, the film gets one thing right. It portrays a tech company in which employees’ identities are so firmly linked to their roles at work, that they pursue the company’s goals without ever thinking of their (the goals) effect on the outside world. The result is surveillance technology that places an extreme amount of extrajudicial power in the hands of the company’s CEO, Tom Hanks. What this film tries–and mostly fails– to portray, is a neo-feudalistic society, in which workers live on an isolated compound with only their fellow employees, living solely for their company, as if it were its own nation with managers acting as vassals.

The road to corporate feudalism isn’t going to be paved by guys who look like Don Draper. Suits and ties and constriction are the ways of the past. The real way to trick someone into spending 100% of their time working, is to convince them that they’re not working at all. It’s important notice how plenty of already successful companies, noticing their employees’ envy, are starting to implement the same types of incentives as their smaller competitors. This isn’t to suggest that there’s some sort of worldwide conspiracy to turn workers into slaves, but rather to shed light on an important trend; namely, that startup culture is being co-opted by plenty of companies as a means of convincing their employees to work longer, harder, and at a rate that doesn’t correspond to their pay. Now more than ever, potential employees have to be vigilant during the interview process. When in doubt, fall back on the old edict: if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

Matt Clibanoff is a writer and editor based in New York City who covers music, politics, sports and pop culture. His editorial work can be found in Pop Dust, The Liberty Project, and All Things Go.

string(7398) "

Startup culture promotes organizational strategy that emphasizes open communication and has a relatively flat hierarchical structure, the primary benefit being a less stuffy work environment. Stereotypically, this laid-back vibe is usually accompanied by amenities ranging from office happy hours to video games to ping pong tables and beyond.

On the surface, it's the ideal workspace, an area in which frequent breaks aren't just allowed, but encouraged. As long as you get your work done, you're free to do as you please. With just 15% of 2015 graduates preferring a job at a large corporation it would seem that this Disney World-ification of the business world is beginning to stick. That said, when these practices are implemented, reality doesn't always live up to the ideal.

For all of startup culture's attempts to make the workplace fun, they often run into various issues regarding, you know, business. When a company spends money on cool perks, this often means one of two things. On the one hand, it's possible that the company is doing so well that they have the extra cash lying around to host sushi lunches and have FIFA tournaments (more on this later). On the other, this can be a telltale sign of a company that's mismanaging its finances and chasing a luxury office life that it can't afford. There's nothing sexy about balancing the books, but that's the thing that keeps the lights on.

Some offices even offer their employees games - like foosball

Some offices even offer their employees games - like foosball

Sometimes though, the scenario is such that a company can provide all of the comforts associated with the typical startup without bankrupting itself. While it sounds great, this isn't necessarily a good thing. Obviously, everyone wants their job to be fun. They want a flexible schedule that allows them to decide when and how their work gets done. But the problem is, when there isn't a fixed schedule or the office is full of toys, it's pretty easy to get distracted, and employees often end up working long hours to compensate for all of the nonessential work events. On top of this, when there isn't a rigid hierarchical structure, people assume there aren't rigid power dynamics. This is a mistake, and when the lines between boss and co-worker start blurring, it becomes a particularly difficult tightrope to walk. Especially since America puts a pretty low premium on work-life balance, and our social lives tend to be spent mostly with our coworkers. This intermingling can feel rather constricting, considering that it leaves very little time to not be on. It can also lead to nauseating conversations with not-your-managers in which they say things like I'm putting on my friend cap. The power dynamics in this world tend to resemble that of a school playground rather than the fixed, almost militaristic structure of 20th century corporate America.

This isn't the only way in which startups buck corporate trends. While they lack in work-life balance and financial stability, startups make up for this by providing people the opportunity to be a part of something from the get-go, allowing people to feel as though they're an integral part of their team. As said and repeated ad nauseum, millennials want jobs that give them purpose, and startups are particularly good at facilitating this desire. This changes the fundamental structure of what a work environment is. Work is no longer a place where one goes and receives payment in exchange for his/her services. The world of the startup is predicated on making its workers' jobs an extension of themselves.

Team building at the office

Team building at the office

The 2017 film The Circle, while so terribly written that it may have destroyed Emma Watson's career, attempts to deal with the problem surrounding tech companies and the cult of personality that tends pervade within them once they hit critical mass. If you ignore the plot, horrible acting, and bad writing, the film gets one thing right. It portrays a tech company in which employees' identities are so firmly linked to their roles at work, that they pursue the company's goals without ever thinking of their (the goals) effect on the outside world. The result is surveillance technology that places an extreme amount of extrajudicial power in the hands of the company's CEO, Tom Hanks. What this film tries–and mostly fails– to portray, is a neo-feudalistic society, in which workers live on an isolated compound with only their fellow employees, living solely for their company, as if it were its own nation with managers acting as vassals.

The road to corporate feudalism isn't going to be paved by guys who look like Don Draper. Suits and ties and constriction are the ways of the past. The real way to trick someone into spending 100% of their time working, is to convince them that they're not working at all. It's important notice how plenty of already successful companies, noticing their employees' envy, are starting to implement the same types of incentives as their smaller competitors. This isn't to suggest that there's some sort of worldwide conspiracy to turn workers into slaves, but rather to shed light on an important trend; namely, that startup culture is being co-opted by plenty of companies as a means of convincing their employees to work longer, harder, and at a rate that doesn't correspond to their pay. Now more than ever, potential employees have to be vigilant during the interview process. When in doubt, fall back on the old edict: if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

Matt Clibanoff is a writer and editor based in New York City who covers music, politics, sports and pop culture. His editorial work can be found in Pop Dust, The Liberty Project, and All Things Go.

"

Some offices even offer their employees games – like foosball

Some offices even offer their employees games – like foosball  Team building at the office

Team building at the office